Area landowners learn timely preparedness lessons as March 6, 2017 wildfire anniversary approaches

An early-morning fire last Sunday in rural Hemphill County destroyed a hay barn and the livestock that were inside, sheltering from below-freezing temperatures. It was a tragic reminder that fire will always be a threat here in the droughtprone Texas Panhandle—one made even more dramatic because it occurred on the fifth anniversary of the terrible wildfires of March 6, 2017, a date whose significance few in this community need any help remembering.

Those who attended the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Wildfire Preparedness meeting, held on Jan. 31 at the Hemphill County Exhibition Center, were also reminded of that historic event. Over coffee and doughnuts that morning, they heard from two AgriLife Extension speakers: Disaster Assessment and Recovery Coordinator Brandon Boughen’s refresher course on preparing for and protecting against wildfire, and Rangeland Resource Specialist Tim Steffens’ comments on the effects of fire.

“You don’t need a picture to show you what you see every day out in your field,” Boughan told the ranchers and landowners who gathered there that day, referring to the rapidly encroaching drought conditions that continue—even today—to threaten most of the Panhandle. “We’re not looking at this going away anytime soon. It’s gonna be here.”

While both Boughen and Steffens offered timely reminders that all Texas Panhandle residents would do well to heed, it was a panel of ranchers, joined later by area firefighters, who drew a standing-room-only crowd that afternoon. Each panelist had a personal story—and a harrowing one—to tell about his encounters with wildfire.

Following a lunch break, Hemphill County AgriLife Extension Agent Andy Holloway introduced the five ranchers who had agreed to share some of what they had learned from their own experiences in the line of wildfire. “All of these gentlemen have either been affected by wildfire,” Holloway said, “or have been part of fire circumstances.”

JOHN ERICKSON

John Erickson—a rancher and author of the beloved Hank the Cowdog series and several other books—led the panel, which included Jason Abraham, Craig Cowden, Cody Mathews and Tim Steffens.

In the March 2017 wildfire, Erickson and wife Kris lost their rural home—located in a canyon north of the Canadian River—as well as his office and most of their possessions. That day, Erickson had driven up the caprock to check for signs of smoke, but hadn’t seen anything. A few minutes after his last trek, though, he got a call from a pumper, who told him he’d seen smoke on the Wilson Ranch, which adjoins theirs.

“The wind was now blowing 40 to 50 miles an hour,” he remembered. “I didn’t need to be told any more. I went inside and told Kris, ‘Get your computer, your mandolin and an overnight bag, and let’s go.’”

Their normal route out of the ranch was already blocked by the fire, which Erickson guessed had covered seven miles in a mere 20 minutes. “It was like an atom bomb going off,” he said. So they backtracked, and drove the other direction, back to US 83 and to their town house in Perryton.

The next morning, after a reconnaissance trip to the ranch, their son called them to deliver the news. The house was gone. So were the office and bunkhouse.

“My job for the past 30 or 40 years has been rocking babies to sleep at night with Hank the Cowdog audio books,” Erickson told a very attentive audience at the Hemphill County Exhibition Center on January 31. “That’s something that I chose to do and love to do.”

When the wildfire struck, he said, “The subject chose me….So that was the beginning of my job.”

The result was a book published last year, Bad Smoke, Good Smoke: A Texas Rancher’s View of Wildfire.

“I didn’t necessarily want to write a book about wildfire,” he said. “I didn’t think I knew anything about it.”

Erickson realized, though, that he’d had a ringside seat to two of the biggest wildfires in Texas history—as a spectator to the 2006 fire, that burned over a million acres in the Texas Panhandle, and now, as a victim of the March 2017 wildfire, which burned 31,145 acres in Ochiltree, Hemphill, Roberts and Lipscomb counties.

“I did a lot of observing about what that fire had done to my ranch,” Erickson said. “I’m a book guy. I’d lost every book that I ever wrote. I lost my grandfather’s irreplaceable library on Texas history. I lost unpublished manuscripts—the three novels I wrote back in the 70s. But I’d been forced to do a lot of thinking about wildfires.”

Erickson thought about the oral history he had learned from his mother’s family, who had settled in the Lubbock area during the 1880s. “They talked about blizzards and grasshoppers and droughts,” he said, “but through four or five generations…in this part of the country, my family never saw wildfires.”

“I wondered why,” he said. “So I spent a lot of time trying to analyze that, and Good Smoke, Bad Smoke is a result of that.”

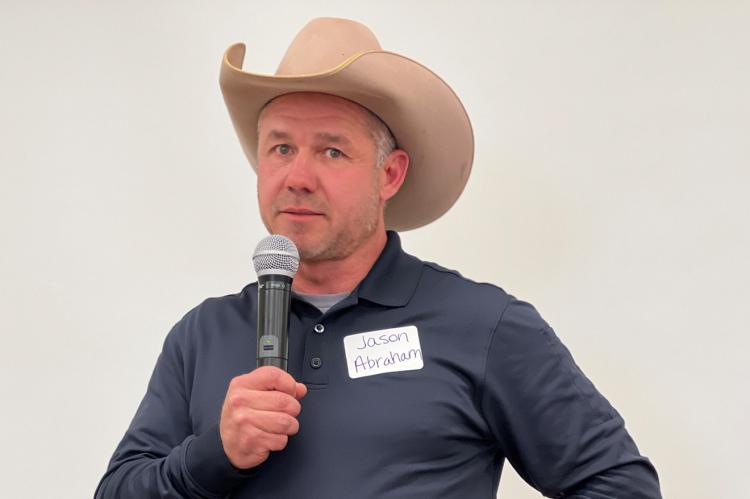

JASON ABRAHAM

Jason Abraham is a Hemphill County rancher, a pioneer in equine and deer cloning, and a helicopter pilot whose aerial firefighting skills have been well-tested and finely-honed years of experience.

“I want to talk about what I’ve seen, what I see every fire, and what I think about when I see this,” Abraham said. “I’m watching you guys drag your cows out, just like I’ll be doing dragging the cows away from the fire. You might see me drop behind you and push them a little bit. And in the back of my mind, I’m thinking about the people I found dead.”

As he hovers overhead in a firefight, Abraham said, he is always hoping somebody below has got a plan. “What I want you to know is there’s a few things we can take away from this… and number one, if you’re on the ground and in your pickup, never leave the vehicle.”

“You cannot outrun a fire,” he said, remembering one specific fire when the people on the ground left their car. “They made it about 100 yards, and that’s where I found them. They got spooked and they made a bad call. You can’t lose your head. You gotta’ be cool. Stay with your vehicle.”

He recalls another time, when a controlled burn had gotten out of control. “I was maybe one or two more helicopter drops off from getting this thing put out,” Abraham said. “I was loading water, and all of a sudden, there was screaming on the radio.”

Abraham said he brought the helicopter around to see fire racing up the hill. “I call it the fire devil,” he said. “I’m about 100 feet off the ground, and this thing is probably 300 feet higher than me, and I’m hearing people screaming and I know who it is. I was going with a load of water to their rig, but they weren’t there. They were down about 400 yards from their vehicle and the fire caught them.”

By the time Abraham arrived, it was too late. “They’d already been burned,” he said. “Both men lived, but were very badly burned. That’s nothing you want to see.”

Two points Abraham hammers home to his audience. Stay with your vehicle—even if it has been disabled, and even if the fire surrounds it. You’re safer than you’ll ever be on foot.

The other point: Somebody needs to know where you are. “Can’t ya’ll send a freaking pin drop? You don’t know how to find yourself on Google Earth? You don’t know what Fly 360 is? There all these ways that we can track and find you.”

“Take a picture of your compass on your phone and give me GPS coordinates. Screenshot it. Send it to me,” he said. “Some of you can’t even turn your freakin’ phone off. Ya’ll need to deal with your grandkids and learn how to do that—just so I don’t have to come find you.”

“Things can go sideways real fast, and you need to have a way out.”

CRAIG COWDEN

Craig Cowden’s ranch is north of Skellytown in Gray County—an area at the dead center of the bullseye in many of this area’s wildfires. Fire is no stranger. His first occurred in 2006, while he was still in college. It burned the ranch up, Cowden remembers. More followed between 2010 and 2016.

“The tumbleweeds had come up in 2014 after the drought,” he said. “They piled in the corners. The cows ran into the corners and it burned them up.”

Cowden convinced his dad to invest in a firefighting skid for the ranch pickup. “We basically turned it into a brush rig,” he said. “So one of the things that we do is we firefight in the skid. It’s one of those things like a handgun: You hope you never have to use it, but whenever you do, you’re glad to have it.”

“I’m going to manage and mitigate to the best of my ability,” Cowden said.

Cowden is also a believer in helping the local firefighters on the front line. Though aware of the dangers, he also realizes that the landowner knows his place better than anybody else. The firefighters’ main objective is to get the head fire shut down.

“You know where the gates are,” he said. “You know where the cattle are. You can tell them about the topography, and where they can fill up with water.”

That information is invaluable to those first responders, Cowden said. “Don’t think that you have to be out there actually fighting the fire,” he advised. “Just help them out.”

CODY MATHEWS

Cody Mathews is a sixth-generation rancher, and a volunteer firefighter, in Lipscomb County. His first wildfire experience was in 2011, shortly after he and his wife had moved back home from Lubbock, in preparation for taking over the family ranch.

Shortly after their return, Mathews said, “we had a wildfire that burned half the place off right before I was going to go to work.”

“I called my grandpa the next day and said, ‘It’s not a good time, is it?’ He said, ‘Well, I sure am glad you said it and not me.’”

Mathews went to work in the oilfield for the next five years before moving out to the ranch in 2015. He joined the Locust Grove Fire Department in 2016, less than a year before the March 2017 wildfire.

“I had a ton of firefighting experience,” Mathews said. “I had been on one small oilfield adventure that took 30 seconds to put out a round bail that was struck by lightning before I got on the firetruck that day in 2017.”

Mathews called it “being baptized by fire.”

He remembers climbing on the truck around 3:30 that afternoon. “They were talking about the fire devils, or fire tornadoes, or whatever,” he said. “There were five in the fire line as we were pulling in, and the first time I got introduced into a fire line, it overtook our truck.”

“We’re not kidding when we say don’t leave a vehicle,” Mathews said. “Our number one rule in the fire department is never leave your truck.”

The head fire that day was moving about 75 miles an hour, according to Abraham. “We’re firefighters and we like to go to the head,” he said. “We like to be the guys that put out the head fire. That fire was moving at 75 mph, and our truck runs 55 to 65 mph.”

It was clear Mathews knew what he was talking about when he warned his audience to be careful. “You’ve got to really, really think about what you’re getting yourself into,” he said. “No matter how well you think you know your place, when that smoke rolls in, you don’t know where you are.”

TIM STEFFENS

More people get killed by smoke or the hot gases than are killed by fire, said AgriLife Rangeland Resource Specialist Tim Steffens, who also ranches in the Wilderado area.

“That’s one more reason why you stay in your vehicle,” he said. “You get in there, and the fire may burn, and it may get pretty dang hot in there, but you can shut the vents and stay out of the smoke and gas. The tires may catch on fire, but by then, the big fire is probably gone.”

Steffens told the story of one team of firefighters in Ordway, Colorado, who were racing to get to the head fire when they crossed a bridge that had burning tumbleweeds underneath. The flames had weakened the bridge supports, he said, and the fire truck fell right through. “It killed them all,” he said, “so be aware of those kinds of things. Always have an alternate route.”

One other word of advice, Steffens said, “and this may go against everything these firefighter will tell you.” He told the story of a wildland fire in Montana. Firefighters were dropped in, and were managing the fire line when the wind shifted.

“It started coming back toward them at a pretty rapid clip,” Steffens said.

When they started running, the crew leader pulled out a box of matches and told them just to start a fire and step into the black. They ran anyway, to the top of a hill—the very worst place you could go, Steffens said.

The crew leader lit the box of matches, and stepped into the black, burned area. “He lived. The rest of the crew died,” Steffens said. “A back fire is fairly tame. You step over that, get out in the middle of the black, and get down low so you’re out of those gases.”

“You may have a little bit of chance,” he concluded, “but you got no chance at all running from the clock.”

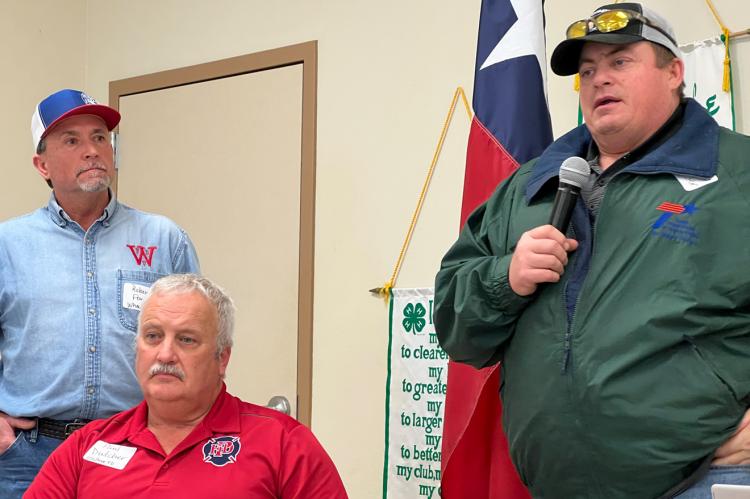

The discussion concluded with comments from three area fire chiefs: Canadian VFD Fire Chief Scott Brewster, Wheeler County Fire Chief Robert Ford, and Ochiltree Fire Department Chief Paul Dutcher. All three departments provide mutual aid to each other, and to other firefighters throughout the Panhandle. Questions and comments from the audience touched on a number of topics, from the importance of being aware of daily drought and fire weather conditions, to the controversial subject of controlled, or prescribed, burns and related liability issues.

Erickson shared some of the research he did, following the March 2017 wildfire, about the history of wildfires in this region, and the natural benefits that wildfires, or controlled burns, may provide in land and rangeland management—subjects his latest book addresses in the final chapters.

This was the second wildfire preparedness event hosted by Hemphill County AgriLife—and co-sponsored by Ochiltree, Lipscomb, Wheeler and Roberts County AgriLife Extension agencies—but judging from attendance, and the interest it generated, is unlikely to be the last.