Hemphill County Task Force delivers $680,000 in donated funds to wildfire victims

Report and photos by Laurie Ezzell Brown

The Smokehouse Creek Fire started about a mile north of Stinnett in Hutchinson County on the morning of Monday, February 26, when a decayed Xcel Energy pole broke off at the ground, downing the power line and igniting the grasses below.

Reports of elevated fire conditions had been issued days in advance by Amarillo’s National Weather Service, which had predicted near-record high temperatures of 80 degrees and winds gusting up to 55 miles per hour on Monday, February 26. It was the grim precursor to the following week’s red flag warnings, the constant blare of fire sirens, and a much too early start to the Texas Panhandle’s dreaded wildfire season.

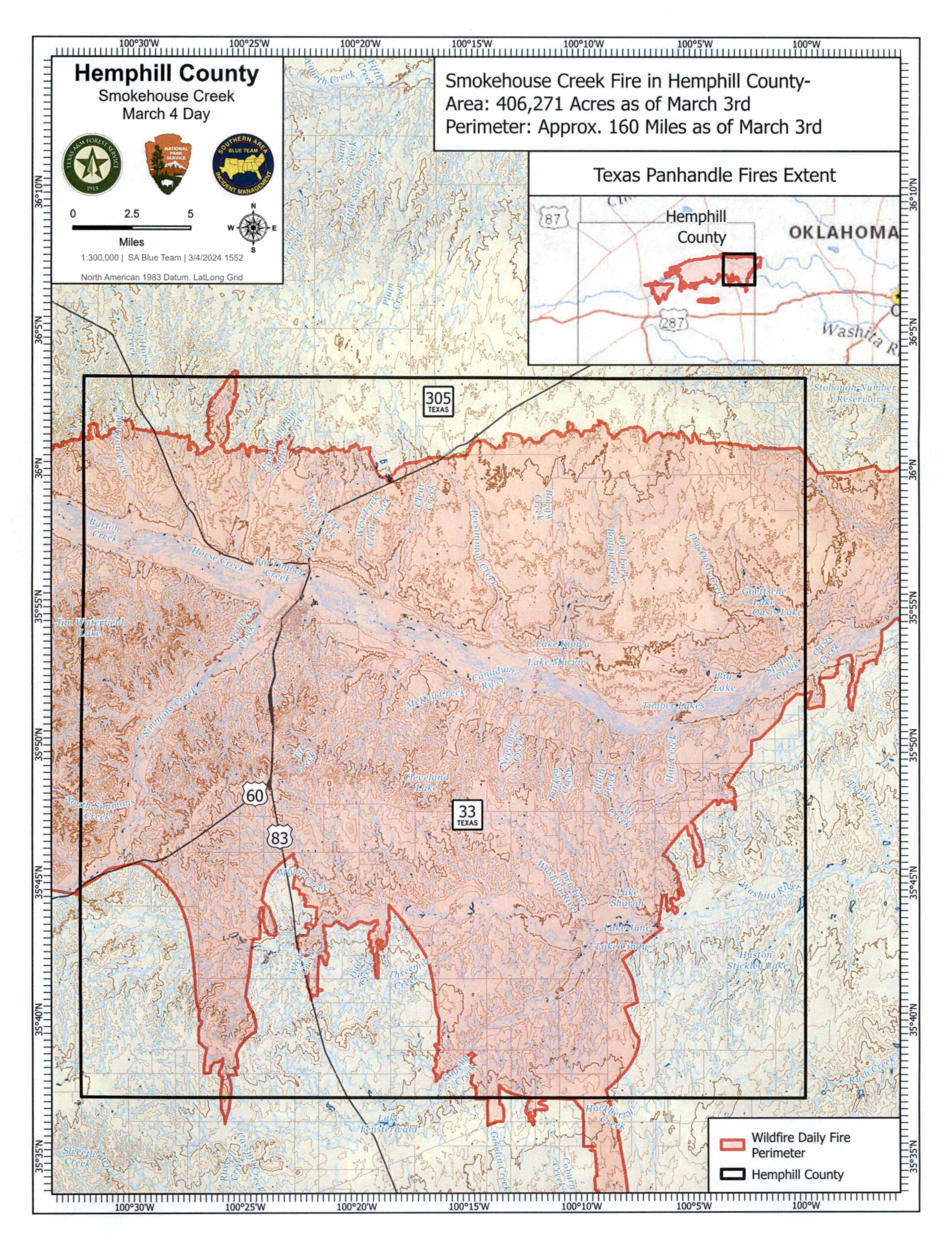

The Smokehouse Creek Fire was only one of five wildfires* that raged through the northeastern Texas Panhandle that day, but it soon earned the dubious distinction of being the largest wildfire in Texas’ history.

Fueled by unseasonably high temperatures and 55-mph winds, and moving at estimated speeds of 6-8 mph, the fire advanced rapidly. Over the next two days, roads were closed and a chain of increasingly urgent evacuations were ordered throughout the area, as the flames burned over 900,000 acres and crossed into Oklahoma.

By the time the Smokehouse wildfire was declared fully contained on March 16, an estimated 1.058 million acres had been burned, including about 80 percent of both Hemphill and Roberts counties.

In a May 1 report to the Texas House Investigative Committee on the Panhandle Wildfires, AgriLife Agent Andy Holloway detailed the damage in Hemphill County alone: 76 homes in or around Canadian burned to the ground or were badly damaged; over 7,000 cows (out of 23,000 in the county) were killed, and an estimated 15-20 percent of the remaining cows would likely be harvested due to burn injuries; hundreds of water wells were destroyed; thousands of native trees have been lost; over 400,000 acres were burned, and over 2,500 miles of fence either destroyed or damaged.

Preliminary estimates placed the value of homes lost at $35 million, of other structures at $13 million, and of other real property at $175 million. Less easily calculated were the loss of livelihoods, economic viability, historic landmarks, aesthetic beauty, and a sense of security.

EVEN AS EFFORTS TO STOP the fire’s spread continued, donations of money and materials began pouring into this area from across the country, sent to help the homeowners and ranchers who had experienced such devastating losses.

In Hemphill County, the response was overwhelming.

Within days, over $1.079 million in donations had already been collected to help those whose homes had been destroyed or badly damaged. Another fund, established to offset the losses sustained by Hemphill County ranchers, had received nearly a million dollars, and was still growing.

Donors shipped over a thousand loads of hay, feed and fencing supplies. More than $3 million in livestock supplies were contributed. In the month that followed, more than 140 volunteers showed up to work—hour after hour, day after day—to help distribute resources to those with losses.

“Just managing the donations—the financial donations as well as the tangible ones—was an unbelievably complicated process,” Hemphill County Judge Lisa Johnson said. “We have had volunteers who worked 12- and 14-hour days, for weeks and weeks—people who have jobs and families, and even the folks who lost homes, were part of the volunteer effort.”

“They didn’t just sit down and wring their hands,” she noted. “They got up and went to work, trying to help their neighbors. It was incredibly touching.”

The job of gathering information documenting the losses had already begun—even as the sirens still sounded—and it was an arduous one.

A TASK FORCE OF COMMUNITY MEMBERS—representing local churches, governmental entities, and the medical, financial and education fields—was quickly appointed to coordinate Hemphill County’s relief efforts. All were pledged to confidentiality.

“There’s been kind of a succession of things that have happened with the response to the fire,” Johnson said. “Of course, the first thing was getting the fire out. The next thing was identifying the people who had lost homes and property and livestock and those kinds of things.”

“The first goal of the wildfire relief task force was to secure temporary housing for those folks who lost their homes—and that was quite an effort,” Johnson said.

By March 1—only four days after the wildfire’s genesis—the group had already compiled an extensive database of those who suffered losses, and distributing small checks to meet the immediate needs of the most vulnerable victims.

Task force members worked tirelessly to contact every single person who had lost homes, or whose homes had been rendered unlivable. Some were hard to reach, having found temporary housing with family or friends, or in other communities. In all, 53 homes were lost, and 23 homes sustained extensive damage.

They also contacted local realtors, talked to those who owned homes or rent houses that were unoccupied. They fielded hundreds of calls from people asking what they could donate, where to send funds, where to deliver donations.

While their situations vary widely, all of those families now have somewhere to live. Some are renting houses that were vacant, some have moved into the Oasis Cove Apartments, some are living in campers temporarily, and some have already purchased or started to build new homes.

“We will continue to reassess those needs, and be in touch with those people,” said one task force member. “We’ve encouraged them to continue to let us know what their needs are. Our goal is to make sure people have long-term permanent housing. That’s the goal.”

A MULTI-AGENCY RESOURCE CENTER (MARC) coalesced at the Hemphill County Exhibition Center, which was designated as the official resource collection and distribution center for wildfire victims. It was quickly flooded with truck- and trailer-loads of donated emergency and household supplies. Wildfire victims who signed in were given $300 checks from the Salvation Army, as well as gift certificates from companies like Walmart and Amazon.

Following Round 1 of the needs assessment process, checks ranging from $2,000 to $5,000 were sent to seventeen families. A week later on March 18, following the second assessment, another family received a check. Within another ten days, five more checks were sent out as the list grew.

Some families returned the checks, asking that they be used to help others with greater needs.

The needs assessment process became more specific. How can we assist you at this point? Has your property been cleared, or do you want it cleared? Do you need furniture? What resources have you received? And again, what do you need now?

Another job the task force has performed has been to carefully document the donations and the volunteer hours that have been so crucial to the wildfire response. “It is incredible that they had the forethought to do that as we entered the donations phase,” Johnson said.

“Being a small county almost gives you an advantage when you’re dealing with an emergency,” she added. “We know the people we’re talking to, and how to get a hold of them. We trust them. I think that goes a long way in dealing with the immediate disaster, and then the response to the disaster.”

As the process continued, the task force gathered other information: Was the home single-family? Manufactured? Livable or damaged beyond repair? Insured? Under-insured? Primary home or secondary? Did the family have children living at home?

These details were documented, verified, and added to a growing spreadsheet of information that would help assess value of loss, and enable the task force to fairly disseminate the money donated.

The process was a difficult one. Many of these families had lost everything.

“These people had this mental weight on them,” one task force member said. “Some of them weren’t even able to process what their future looks like.”

“There is a level of shock, too,” said Judge Johnson. “The immediate response we got from some people was, ‘We’re okay.’ And I think what that meant was, ‘We physically were here.’ But we all knew, you’re not okay. You’ve lost a home, and that means that you have a lot to deal with—not just financially, more so even emotionally, and especially those who have kiddos. Dealing with all of that is just heartbreaking.”

Much of the data was collected in compliance with Texas Department of Emergency Management’s (TDEM) Individual State of Texas Assistance Tool. iSTAT, as it is called, allows individuals to report damages to private homes and businesses, and assists emergency management officials in assessing damages.

“TDEM was here early on Tuesday when the fire was just reaching Hemphill County, and coming toward us,” Johnson said. “They got here quickly, and we got our emergency operations center set up. They helped walk us through a lot of decisions that needed to be made, and the resources that we were going to need.”

“They were here for three weeks,” she added, “and those agencies don’t leave until the county judge says we don’t need your services anymore. They are still helping us with the Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG).”

That grant will reimburse the county for the expenses incurred dealing with the disaster, as well as some of the expenses for the volunteer fire departments, and possibly those sustained by the hospital and city. Having a detailed database of all wildfire response costs is essential to meeting the FMAG’s $2 million threshold for expenses.

Because all of the volunteer work and donated resources and expenditures were so carefully tracked, Johnson said, “We believe we have met that threshold. That’s a 75/25 matching grant, and we can use in-kind donations as part of our 25 percent.”

LAST WEEK, IN HEMPHILL COUNTY, a total of $680,000 in checks was delivered to all whose homes were destroyed or badly damaged. Those funds followed an initial $2,000 in funds delivered to each family in the first week to help with immediate needs. An additional nearly $420,000 in donations remains.

“The taskforce is holding on to some of those funds,” Judge Johnson said. “We think we can work with some after-disaster groups that can help us with families who will struggle to secure permanent housing, whether they want to rebuild, or rent long-term—whatever they are able to do.”

“Some will need considerable help over the next six months to a year or two, to get into some type of permanent housing,” Johnson added.

Other wildfire relief donations—last estimated at about $1 million—have been collected by local churches and distributed to families in need.

When asked how the community has been able to get through a disaster of this scale, Johnson found the answer was simple. “People came running to this fire,” she said. “Local people and Panhandle people and the state of Texas and the country, people came running to help us survive.”

“Very quickly, incredibly quickly, people were focused on gratitude,” she said. “Gratitude is what keeps us in the present moment. We were able to say we are grateful for what is left, and we’re grateful that our people are alive, and that we have the help and support of so many people. And I just keep hearing gratitude. That’s really what has sustained us over the last couple of months."